Ok, TDD sounds great, but...

7 min read - 2020-05-04

After reading my last post, Yes, tdd does apply to your usecase, my friend Ruskin gave me very interesting feedback.

He pointed out some existing flaws of my proposed solution. This was great. I don’t believe in software as something individual and done once and forgotten forever. At least, that was never how it worked for me in the real world.

I got so intrigued about the feedback that I had the dilemma: Should I edit the last post? Or write a new one?

Instead of editing, which would mean losing the initial thoughts, I thought it would be great to explain how to improve, and the rationale behind it. Here we are.

What feedback did I get?

It was essentially two things:

- Some myths about TDD were listed as wrong, but missing the why

- I referred to interface first software design, but didn’t follow it as much as I should in some parts

Debunking the myths

Before changing my mind in regards to TDD, I tried it a couple of times. I always ended up thinking that:

- I can’t write all the tests upfront, that’s impossible

- I can write the tests afterward and still not be biased, it is pretty much the same thing, right?

These are two very common misconceptions about TDD, and even though I listed them in my last post, I failed to explain why they are wrong.

That’s what we’re here for.

I need to write all the tests upfront

This was always my thought since I first read about TDD. I’ve seen these people who used it as some kind of magician. They seemed to know everything about how they would code their features from the first moment. I couldn’t do it.

After reading the book, it was clear to me that those kinds of magicians do not exist, or at least they’re very rare.

Again, quoting Kent Beck:

I’m not a great programmer; I’m just a good programmer with great habits.

Those magicians just had better habits, and they knew how to use them to design better and to produce easy to change software.

A few chapters in the book, and I was starting to feel the magic. The tools were helping me, being more specific, the tests were helping me to design better and to test my ideas faster. I also didn’t have to wait for the implementation to discover some design flaws as they were clear from the start. That blew my mind 🤯.

TLDR: No, you don’t need to write all the tests upfront. You need to write the simplest meaningful test for the feature you’ll implement. Implement it, and come back to write the next test when this one is green.

You do write tests before coding, just not all of them. To me, the secret was to keep this short cycle of writing a test and the logic for it, multiple times until the feature is done.

I can write the tests afterwards

You actually can, and that’s what I did most of the time. I thought I wouldn’t be biased, I wouldn’t end up testing implementation details. I’m not here to trick myself, right?

I’m sorry to say this, but I was completely wrong.

What happened (and still happens if I don’t write the tests first) is that I know too much about the implementation for that not to influence me when testing.

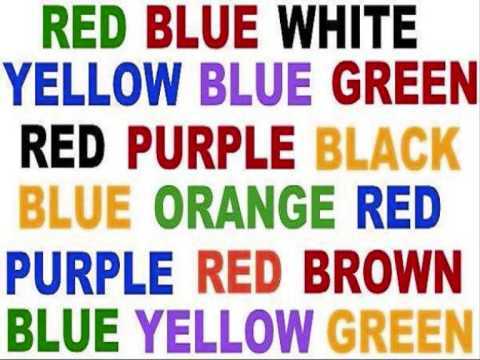

It was a little like the following exercise:

Try to say the underlying colors and not the words.

Tough job, right? Your brain automatically reads the words while you’re trying to say the color.

Quoting Daniel Kahneman on Thinking fast and slow:

“System 1” is fast, instinctive, and emotional; “System 2” is slower, more deliberative, and more logical.

The instinctive part of the brain (System 1) is tricking you. You want to say the underlying colors, but your mind automatically reads the word, unconsciously. This is how testing last was to me.

It also felt like starting to do something without a clear goal in mind. Let me quote Seneca (yes, I like quotes) in a saying that is very common in my hometown, the fishing village Ericeira:

There is no favorable wind for the sailor who doesn’t know where to go

By writing tests first I noticed I was putting the bar much higher before writing my logic, and my completion criteria were clear from the start.

TLDR: You can write tests last, yes. But do not expect most of the TDD advantages. It is the fact that you do it first that makes it so effective, it’s a matter of discipline more than anything else.

Going “interface first”

In the last post, we wrote a failing acceptance test for the feature we were writing.

// cypress/integration/stock.ts

import { Server } from "miragejs";

import { makeServer } from "../../makeServer";

let server: Server

beforeEach(() => {

server = makeServer({ environment: "test " })

})

afterEach(() => {

server.shutdown()

})

it("renders wine names", () => {

cy.visit("/")

server.get("/wines", () => [

{ name: "Pomares", year: 2018 },

{ name: "Grainha", year: 2017 },

])

expect(cy.contains("Pomares 2018")).to.exist

expect(cy.contains("Grainha 2017")).to.exist

})After that, we went on the quest to write the logic to satisfy it. I mistakenly jumped to conclusions, skipping some intermediate steps, and stating that we would need an API client.

If I strictly followed the principle I advocated (going interface first), I shouldn’t have done it. I should have first started by testing the component, and only get to the API client when it was strictly needed.

Doing a small recap:

The first thing after the acceptance test should be to write a failing unit test for the component.

// pages/index.test.tsx

import { render } from "@testing-library/react"

import { Home } from "./index"

it("renders", () => {

const { getByText } = render(<Home />);

expect(getByText('Wine Cellar')).toBeTruthy();

expect(getByText('Available Stock')).toBeTruthy();

})Then we would realize the need to connect to an API and thus the need for an API client.

// pages/index.test.tsx

import { render } from "@testing-library/react"

import { Home } from "./index"

import * as Api from "../services/api"

it("tries to get wines", () => {

const getWines = jest.fn()

// @ts-ignore

Api.getWines = getWines

// ts-ignore is needed to be able to mutate the `readonly` property

render(<Home />)

expect(getWines).toHaveBeenCalled();

})From here onwards, the whole flow would come up naturally. First by creating the API client tests, then the logic itself, and later use it on the component that needed to fetch the data. You can see the rest of the flow here.

With the proposed changes, the flow strictly follows the interface first principle, making it more intuitive to follow and improve the overall code design.

Conclusion

I hope to have answered some questions that were left floating the last time I wrote. At the same time, I wanted to demonstrate that both writing and software are iterative and feedback-driven processes.

This post also writes down the precious knowledge that Ruskin shared with me (many thanks for that 🙏). The noted problems and doubts were probably common in other people too, and I hope to have made them clear by now

Are you still not convinced by TDD? What problems do you have using it? Doesn’t it apply to your use case? 😉

Feel free to reach out to me, I’d love to hear from you